The Grand Design

by Stephen Hawking and Leonard Mlodinow

(Bantam Books, 2010)

Stephen Hawking, along with Leonard Mlodinow, has written a fascinating new book entitled The Grand Design. It has been the subject of intense media attention, not least because he appears to argue that God is not needed to explain the origin of the universe.

Stephen Hawking, along with Leonard Mlodinow, has written a fascinating new book entitled The Grand Design. It has been the subject of intense media attention, not least because he appears to argue that God is not needed to explain the origin of the universe.

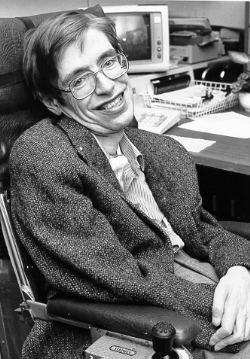

Hawking is a remarkable and iconic figure; a genius trapped in a disabled body, confined to a wheelchair, using a computer synthesizer to speak. The sound of that speech, which we know so well, has an uncanny effect. It is a sort of oracle for our times. So when he speaks, or writes, people sit up.

His book, beautifully produced and with stunning art work, is a good read. In his first chapter he helpfully outlines the way in which knowledge of the world is traditionally obtained; through direct observation. However, with the rise of modern physics we find concepts that clash with our every-day experience and so we have to alter our ‘naïve’ view of reality. Our model of the world, which we obtain from our sense organs, is only one way of understanding reality. We now have to make new models which may be just as true. This of course leads later into the extraordinary and counter-intuitive world of quantum physics. His chapters on this are well worth the effort to read.

Considering the weight of the topic, this is a short book and he swiftly leads us into M-theory, which is his current favourite for explaining the nature of reality and, crucially, how the universe may have begun.

The multi-dimensional M-theory is clearly a view of reality to which some versions of mathematics and physics point. While not actually unifying all the laws of nature, it seems, to Hawking at least, to supply many answers to the way the universe came into being - not just how but why it began. And this is the controversial bit; if we can explain why it began, then perhaps we can do away with the need for a Creator. We ought to say here, though, that he does not actually deny the existence of God at any point; rather he implies that God is not needed to make the universe.

While agreeing with the fact that our universe is uncannily fine-tuned and appears ‘set-up’ for life, he uses the multiple universe model to allow for such an unlikely set of laws to occur somewhere amongst the trillions of possible universes. He emphasises that the multi-universe idea is not cooked up but is a consequence of M-theory.

Very early on (p.5) he makes the provocative statement ‘….philosophy is dead’. In doing so he elevates scientific enquiry above the work of philosophy, maintaining that philosophy has not kept up with modern developments in science. Now this could be taken as a great insight, or, for me at least, more like a warning of what is to come in the rest of the book. Philosophy, in fact, is thriving just now. My own particular interest, that of Philosophy of Mind, is one the most intensely fertile arenas of thinking that one could hope to find. Here may be a key to the book as a whole; either he is right about philosophy being dead or he is suffering from a severe case of scientific hubris.

Concerning the laws of the universe he discusses their origins (p. 29). He acknowledges that great minds such as Kepler, Galileo, Descartes and Newton believed the laws were the work of God. If so, writes Hawking, then God could perform miracles, that is, be able to make exceptions to these laws. Hawking gets philosophically unstuck here however. He says that science is now based on the adherence to unbreakable laws (not miracles); this is the determinism of Laplace (p. 30). The basis of modern science, he says, is to assume that laws are what determine how things are. Hawking in a circular manner, uses this to deny both miracles and any Creator of the laws. So, science works because of laws that are not broken; therefore there are no miracles and therefore the laws do not come from a Creator. Notice that at no point in this explanation has he given the reader the slightest idea of where the laws have originated. They just exist. Two things can be said here: firstly Hawking has not explained the origin of the laws; and secondly, science in no way excludes, however rarely, exceptions to these laws occurring if the designer of the laws so wishes.

Concerning the laws of the universe he discusses their origins (p. 29). He acknowledges that great minds such as Kepler, Galileo, Descartes and Newton believed the laws were the work of God. If so, writes Hawking, then God could perform miracles, that is, be able to make exceptions to these laws. Hawking gets philosophically unstuck here however. He says that science is now based on the adherence to unbreakable laws (not miracles); this is the determinism of Laplace (p. 30). The basis of modern science, he says, is to assume that laws are what determine how things are. Hawking in a circular manner, uses this to deny both miracles and any Creator of the laws. So, science works because of laws that are not broken; therefore there are no miracles and therefore the laws do not come from a Creator. Notice that at no point in this explanation has he given the reader the slightest idea of where the laws have originated. They just exist. Two things can be said here: firstly Hawking has not explained the origin of the laws; and secondly, science in no way excludes, however rarely, exceptions to these laws occurring if the designer of the laws so wishes.

On the heels of the above explanation, he strays into Philosophy of Mind in asserting in a few words that the determinism of physics out-rules free-will (p.31). He has little understanding about the arguments surrounding free-will and gives no explanation other than a bland assertion that everything is determined. This is worse than poor philosophy. One might then ask him how he can be so sure of his arguments if he has no choice about them.

Concerning M-theory he writes at one point (p. 117): ‘People are still trying to decipher the nature of M-theory, but that may not be possible.’ It is important for the reader therefore to understand that this theory is not really understood and indeed is far from being accepted by all physicists, nor is it fundamental because it does not unite all the laws of physics. It is a mathematical model involving string theory, multiple dimensions (eleven) and varying possibilities for physical laws (and thus different universes). As Roger Penrose, who is perhaps more qualified than anyone else, writes concerning the conclusions of Hawking in this book: ‘I doubt that adequate understandings can arise in this way. This applies particularly to ‘M-theory’, a popular (but fundamentally incomplete) development of string theory…’ [1] M-theory is on the table for discussion but certainly not the final solution. In this context, it may be interesting, but is hardly the basis upon which to make grand theological statements.

Hawking uses the theory to allow for gravity creating a universe from nothing. He writes (p. 180): ‘Because there is a law like gravity, the universe can and will create itself from nothing……Spontaneous creation is the reason why there is something rather than nothing, why the universe exists, why we exist, It is not necessary to invoke God to light the blue touch paper and set the universe going’. Yet, once again the reader asks where the gravity comes from? Are we being stupid and not following the great mind of Hawking? I have looked long and hard at this and come to the conclusion that Hawking has completely over-stepped his authority here. He seems to have little grasp of the actual issue about something existing (such as gravity) rather than nothing. As John Cornwell, director of Jesus College, Cambridge writes: ‘If the law of gravity ‘caused’ the Universe to come into existence, it is nonsense to say that the Universe came from ‘nothing’. Surely the law of gravity counts as ‘something’? Hawking has not explained why something came from nothing.’ [2]

I am left with an admiration for his work in science but a feeling that he should stick to what he is good at and avoid pontificating. Read the book but do not expect any answers concerning a Creator.

Dr Antony Latham

November 2010

[1] Roger Penrose, Financial Times 04.09.2010

[2] John Cornwell, London Evening Standard 03.09.2010

Image credits:

Thumbnail - © Bantam Books

Book cover - © Bantam Books

Stephen Hawking - NASA, Public Domain

Antony Latham, 20/07/2017